Andrzej Wajda has managed a daredevil-like achievement. Not only did he decide to make a biographical film about a living person, but the person in question is a real legend in Poland’s relatively young democracy. Lech Wałęsa is known for his powerful character, attitude, and dashing personality, a mixture of omnipotent pride, stubborn quarrelsomeness, a sense of infallibility, and the capacity to carry out real nation-changing accomplishments. Without these features (and without his characteristic moustache, obviously) it would have been impossible for him to become the symbol of an entire country and one of the very few individuals responsible for the changes that occurred these past decades. Wałęsa. Man of Hope (Człowiek z nadziei) fits perfectly as the third part of a trilogy comprising Man of Marble (Człowiek z marmuru), from 1976, and Man of Iron (Człowiek z żelaza), from 1981. Although filmed some thirty years later, Man of Hope manages to evoke the spirit of Gdańsk’s restless streets, its people, and its poor shipyard workers, all on the verge of single-handedly beheading communism throughout the whole Eastern Block.

"Andrzej Wajda has managed a daredevil-like achievement. Not only did he decide to make a biographical film about a living person, but the person in question is a real legend in Poland’s relatively young democracy."

This part of Polish history seems widely unknown or ignored around the world. On the subject of opposition to the Soviet regime, people are most frequently reminded of the role of Germany and the German Reunification (1989-1990). In fact, the date celebrated worldwide as the beginning of the end of the Soviet Union is the fall of the Berlin Wall. However, almost a decade earlier, in the summer of 1980, certain events in Poland reversed the course of history and left a mark on generations to come. These are the days that Wajda attempts to reproduce, and it is truly captivating.

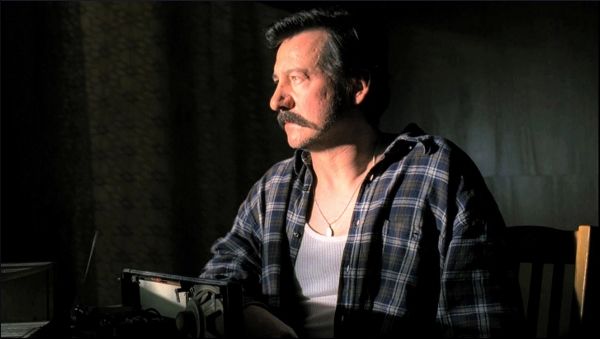

Robert Więckiewicz, one of Poland’s top actors (known for powerful appearances in Vinci, by Juliusz Machulski, and In Darkness, by Agnieszka Holland), impersonates the famous mustachioed former electrician with great flare and a keen eye for detail. One of the first scenes takes place in Wałęsa’s tiny apartment in the Gdańsk’s district of Zaspa, as the future president is interviewed by the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci. Więckiewicz is almost unrecognizable. He is not just an actor emulating the main hero of the story, but seems to have become Wałęsa himself. He impeccably imitates the real man’s characteristic tone of voice – a little nasal, with sounds that reveal his modest upbringing –, his at times inadequate choice of words, and all his mannerisms and quirks. It is like seeing the president live before our eyes, except thirty years earlier. Więckiewicz’s authenticity is also evident when he recognizably repeats some of Wałęsa’s famous slips of tongue. It is particularly fascinating to hear the actor uttering the notorious “Nie chcem ale muszem” phrase, the sense of which is completely untranslatable into English. In short, it means “I don’t want to, but I must,” with the characteristic “m” consonant at the end, which is actually grammatically incorrect. The proper version would read, “Nie chcę, ale muszę.” Yet, said correctly, the phrase would probably not carry as much weight as it does.

"It is no wonder that Man of Hope garnered worldwide recognition and glowing reviews after premiering at the Venice Film Festival."

Więckiewicz’s on-screen partner, the very talented actress Agnieszka Grochowska, plays Wałęsa’s real-life wife, Danuta. Grochowska’s task is not easy, as Mrs. Wałęsa was never a simple First Lady performing ornamental duties, but rather a resourceful handler standing alongside her husband. She was the one who took care of eight children (!) while Lech was away, and she was the one who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, when the honorable recipient, her husband, was unable to leave the country. Years later, she published her bestselling memoir, Marzenia i tajemnice (Dreams and Secrets), in which she recounted her rather lonely years spent as Wałęsa’s wife. It stirred considerable unease, to say the least, but it was generally highly-praised. Because of this book, Grochowska was put in a rather difficult position, since she could not let Wałęsa overshadow her Danuta, and allow Więckiewicz’s portrayal to dim her own brilliant turn. She managed both obstacles with grace and composure.

Apart from the superb performances, the film is filled with many legendary quotes, like “Trzeba mieć w sobie wiele gniewu, by powstrzymać święty gniew ludu” (You have to have a lot of anger inside you to stop the sacred anger of the people), and reenactments of many significant gestures, like Wałęsa undersigning the Gdańsk Agreement of 1980 with a great pen decorated with a picture of Pope John Paul II on its side. The eloquent precision with which these scenes are executed encourages one to admire Wajda’s and his team’s compelling storytelling skills. It is no wonder that Man of Hope garnered worldwide recognition and glowing reviews after premiering at the Venice Film Festival. Yet, the hero of this story, Lech Wałęsa himself, was not entirely convinced. When asked what he thought of the film, he simply uttered, “Ja takim bufonem nie byłem, takim zarozumialcem” (I was never such a bighead, such a stuck-up twit). Well, one could not hope for a better recommendation.