Amores Perros, among its many achievements, helped launch the careers of director Alejandro González Iñárritu and actor Gael García Bernal. For both, this film was their big break: Iñárritu, who had previously only made a few shorts, went on to work with Hollywood stars like Brad Pitt, Cate Blanchett, Naomi Watts, and Sean Penn in Babel and 21 Grams; while Gael García Bernal, who before had mostly acted for Mexican television, would later appear in many more high-profile international movies, including Y tu mamá también, The Science of Sleep, The Motorcycle Diaries, and No. Mexican cinema, meanwhile, enjoyed a moment under the spotlight. Released in 2000, Amores Perros was very well-received by critics and audiences, and even got an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. Even today, it remains one of the most well-known examples of Mexican cinema ever made. The original Spanish title is actually a subtle play on words, since Amores Perros (literally, "loves dogs") sounds the same as "amor es perros" (or "love is dogs"). This can be interpreted literally, since the lovable pets are everywhere in this movie, or more metaphorically, as in "love sucks" or "love's a bitch." The latter was even suggested in some of the movie's English-language promotional material, although the Spanish-language title was used for international distribution.

"Even today, it remains one of the most well-known examples of Mexican cinema ever made."

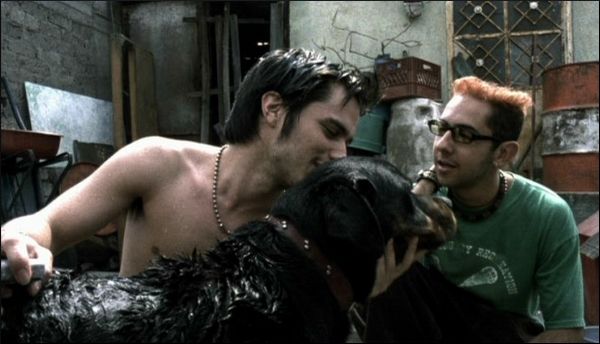

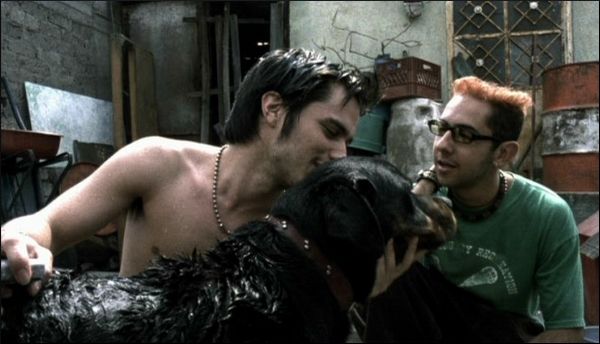

In a way, Amores Perros is not just one film, but three. A horrible car crash connects the stories of Octavio, Valeria, and El Chivo, which are otherwise independent of each other. The first tale is about a young man, Bernal’s Octavio, who falls in love with his sister-in-law, Susana, and promises to run away with her. He gets into the dog-fighting business in order to earn the necessary cash, but certain unfortunate events force Octavio to flee from the criminal elements who have become his colleagues. During the ensuing car chase, he crashes into a supermodel’s car, and thus begins the second tale. Valeria, the beautiful young victim, sustains a crippling injury that eventually forces doctors to amputate her leg, effectively severing her modeling career. For the next half hour, we watch as she copes with the loss of, not only her leg, but also her future and livelihood. Among the witnesses of the car crash is El Chivo, a former professor and revolutionary who, after 20 years in jail, has become a vagrant. He travels through Mexico City with his troupe of street dogs and carries out contracted killings. Beneath his homeless exterior, he is actually a hitman, as well as the star of the third and final tale.

This narrative structure allows Iñárritu to portray the Mexican capital from various perspectives. Not only do the characters change, but also the places they visit and the words they use. Octavio’s journey leads us through run-down apartments and seedy dog fighting arenas, and the slangy speech he uses with his friends and relatives colors the first hour of screen time. Audiences get to hear the many creative uses of “chinga tu madre” and “cabrón,” common insults in Mexican Spanish, along with many other examples of regional vocabulary. For instance, “güey,” which means “dumb or “slow-witted” and is derived from the Spanish word for ox, “buey.” Another interesting word is “pendejo,” which means “stupid,” although friends can use it to refer to each other without taking offense. Interestingly, “pendejo” means “keen” and “smart” in Peru and “kid” or “adolescent” in Argentina, so it’s quite a chameleon term. Other words used by the youths of Amores Perros are “ojete,” similar to English-language insults like “douche bag” or “asshole,” and the phrase “un chingo,” which means “a lot.” And that’s just in the first scene in the movie!

"The movie, in part, is about how people speak and what that says about them, how language suggests both social standing and cultural origins, even those origins the years have tried to forget or erase."

When we meet the other protagonists, the language used is dramatically different. Valeria and her boyfriend are high class lovers who live in a posh apartment, and their Spanish is standard, conventional, and largely devoid of slang. Indeed, Valeria comes from Spain, and although she has spent many years in Mexico, her European accent emerges in dramatic moments. Similarly, El Chivo, despite his current poverty, is an educated man. He might be dressed in grubby rags, but a part of him is still the same University teacher he used to be in the seventies. Near the end of the movie, El Chivo breaks into his daughter’s house, which is empty, and since he hasn’t spoken to her in decades, he leaves a lengthy message on her answering machine, which doubles as the film’s closing monologue. In this moving speech, the teacher and the hired killer combine, and the words of the thoughtful younger man mix with the sadness of the time-weathered assassin. The movie, in part, is about how people speak and what that says about them, how language suggests both social standing and cultural origins, even those origins the years have tried to forget or erase.