The Lives of Others, by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, was one of the first big-budget dramas to deal with the surveillance programs carried out by the East German secret police, known as the Stasi, before the German reunification of 1989. The Stasi was the “Shield and Sword” of the Socialist Party, operating through informants, interrogations, and wiretappings; inspiring paranoia and distrust; and incarcerating people at a whim, for anything from telling an anti-establishment joke to planning an escape to the West. The Stasi successfully put into place an extensive network of civilian employees who were often pressured into (or rewarded for) spying on their friends and family. The information collected was meticulously catalogued in personal files, which the Stasi possessed on virtually every citizen of the republic. After reunification, every citizen was given the opportunity to read his or her own Stasi file, causing many friendships and relationships to break over the shock of having been informed upon.

"The Lives of Others was one of the first big-budget dramas to deal with the surveillance programs carried out by the East German secret police, known as the Stasi."

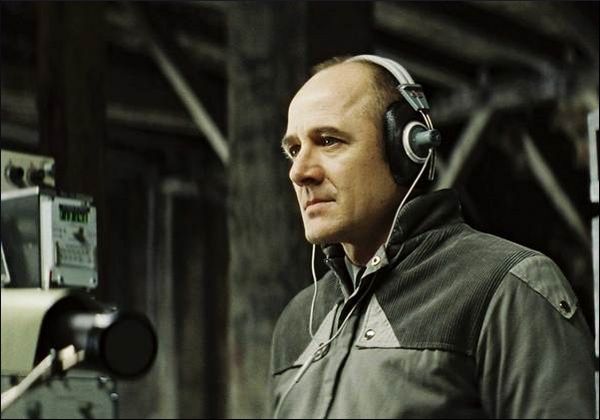

The film begins in East Berlin, in the year 1984 (a none-too-subtle wink to George Orwell’s famous dystopian novel). The aging Stasi captain Gerd Wiesler (the iconic Ulrich Mühe in his last role) is tasked with surveilling a prominent East German writer named Georg Dreyman, whose clean slate and sprawling artistic connections stir suspicion in the high ranks of the party. The task is dutifully embraced by hard line professional Wiesler. He and his team break into Dreyman’s apartment and set up a system of bugs and wiretaps to trace the writer’s every move. Wiesler, however, soon discovers that the Minister of Culture, who was responsible for bringing Dreyman to the Stasi’s attention, has a personal rather than a political motive for opening up the investigation. He wishes to gain sole access to Dreyman’s wife Christa-Maria, whom the minister has already pressured into regular sexual encounters.

Wiesler’s ideological armor begins to crumble as he watches the vibrant life of an artistic community, whose relationships are marked by empathy and affection, emotions Wiesler himself lacks. Conflicted by the un-ideological nature of the surveillance, as well as by the ruthless manner in which the minister treats his subjects, especially Christa-Maria, Wiesler gradually beings to empathize with his victims. In a severe breach of protocol, he begins to cover up their evident disillusionment with the East, failing to report their comments and actions. Meanwhile, Dreyman, enraged by the suicide of a friend, a blacklisted theater director, begins to dangerously oppose the regime, threatening to put himself and those around him at great risk.

While German cinema is perhaps notorious for its constant, and at times over-indulgent, use of wound-licking as its primary source of inspiration for big-budget productions, Donnersmarck manages to make The Lives of Others into one of the most enthralling, well-paced, effective films of its kind. The script skillfully manages to keep the melodrama from galloping out of proportion, the performances are brilliant, and the cinematography is impeccably unaffected. No one can film an interrogation better than the Germans, and interrogations are what this film is essentially composed of, as conversations between characters always mimic the dynamic of interrogations. Characters have to employ the right words, lest they face the consequences of choosing the wrong ones. When Dreyman asks the Minister of Culture to remove his friend, the theater director, from the blacklist, he uses the term “Berufsverbot” (work ban). He is instantly assured, by the cynical minister, that something like that does not exist in East Germany and that, therefore, the word should not be used.

"The film was, without a doubt, one of the most talked about of 2006."

Everyday speech is also littered with recurring acronyms, all of them common at the time. Obvious and famous examples are “DDR” (Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or German Democratic Republic) and “StaSi" (Staatssicherheit, or State Security). Less obvious examples include: “IM” (Inoffizieller Mitarbeiter, or unofficial employee, referring to the Stasi’s civilian informers), “ZK” (Zentralkommitee, or Central Committee), “UV” (Untersuchungsverfahren, or Investigative Procedure), and "OTS" (Operativ Technischer Sektor, or Technical Operational Sector, a Stasi sub-department responsible for the creation and placement of surveillance devices). Wiesler himself speaks in a calm and accurate manner, using words typical of the regime, like "Republikflucht," which literally translates as “flight from the republic” and describes an illegal escape to the West. Mühe brilliantly portrays a hollow man whose words are no more than extensions of a decaying ideology, unemotional mantras memorized to the point of not being up for dispute.

The film was, without a doubt, one of the most talked about of 2006, provoking the ecstasy of most film critics and inspiring record-breaking grosses, as history teachers dragged their bored classes to see it. The Lives of Others also won multiple awards, most notably an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, as well as German Film Prizes for Best Picture, Director, and Actor. The realism of the film’s depiction of the Stasi has been debated to death by everyone with an Internet connection, but the beauty of the movie lies not in its pretence of historical accuracy but in its skillfully narrated tale of redemption. The Lives of Others is a story first and a sermon only to those looking for one.