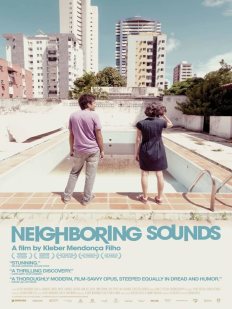

Directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho, O Som ao Redor (released as Neighboring Sounds in English) might be the most acclaimed Brazilian film since Fernando Meirelles’s City of God. Literally, the title translates into “the sound around.” Not “around” something specific, but in a more general surrounding space. Since premiering at the International Rotterdam Film Festival in 2012, the film has garnered critical raves all over the world, and in August 2013, it finally screened for the first time in Brazil. Even with little more than ten copies in circulation, it has already been seen by a good amount of people, and recently, Brazil selected it as its submission for the foreign-language category in the Academy Awards.

"Neighboring Sounds might be the most acclaimed Brazilian film since Fernando Meirelles’s City of God."

Nevertheless, though it has become a big sensation in the last two years, this is a very personal film. Kleber filmed it in Setúbal, his neighborhood in Recife, the capital of the state of Pernambuco in northeastern Brazil. Like in his earlier shorts – Vinil Verde, Eletrodoméstica, among others – he shows an interest in the intimacy of the middle class, closely observing their daily lives and behaviors with his camera. In this district of Setúbal, many characters make up a collection of small stories tying into a kind of ensemble drama (a little bit like the movies of American filmmaker Robert Altman). Various problems and annoyances sprout up among them: the barking of a neighbor’s dog, the sound of a salesman offering pirated CDs, the noise of a stolen car, and so on. These events weave an everyday reality of sounds and noises, fences and walls, streets and roofs, spaces and boundaries.

This is a film about urban paranoia, about fear originating from the historical past of a country. In interviews, Kleber has mentioned how his film can be a powerful tool and how it has the power to reach people. Neighboring Sounds touches on several subtle aspects of Brazilian society, all synthesized within the limits of a neighborhood. Kleber admits that his film subverts the expectations of “reaças” viewers, a short term referring to people who are extremely conservative and reactionary. This way, the movie attempts to help audience members rethink their own prejudices. One scene, for example, is dedicated to the theft of a car stereo. Nobody knows who’s responsible for the crime, although the protagonist suspects the perpetrator is a white youngster named Dinho. He is the type of boy Brazilians often call “filhinho de papai” (daddy’s son), because he thinks he can do whatever he wants since he has a wealthy family to protect him. As this scene reveals, not every thief is black, no matter how much a racist society like the one in Brazil wants to believe so. Some reviewers have compared Neighboring Sounds to the work of Glauber Rocha, the most famous filmmaker to emerge from Brazil’s Cinema Novo (or New Cinema) during the 1960s. Personally, I see nothing here that resembles Glauber Rocha. I see much more of French filmmaker Claude Chabrol, with his sensitivity and gradual discovery of veiled crimes. Neighboring Sounds is a chronicle of the bourgeois of our time, and a brilliant one at that.