- Pedro Páramo

- Published by: Fondo de Cultura Económica

- Level: Advanced

- First Published in: 1955

A classic of Mexican literature, chronicling the rise and fall of a rural landowner, named Pedro Páramo, whose greed and ambition ruins the town of Comala, shaping it into a ghostly collection of windswept buildings inhabited by disembodied murmurs.

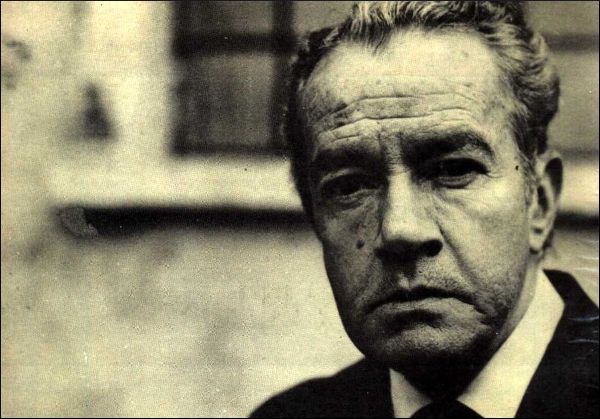

Released in 1955 to little fanfare, Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo has since become a landmark in Mexican literature and one of the most influential books ever published in the Spanish language. It chronicles the rise and fall of the main character, who starts out as a poor boy in the rural Mexican town of Comala, and who eventually becomes the richest and most influential man in the region. The story is set in the early 20th century, and Pedro Páramo even plays a small part in the Mexican Revolution, not due to any political convictions but because of pragmatic self-interest. Greed and hubris drive Pedro into financial and spiritual ruin, and along with him fall Comala and all its inhabitants. Through dreamlike and fragmentary passages, the novel weaves together the voices of many men and women, among them Pedro Páramo, and together they tell the epic of a town’s collapse. All that and more, in 132 pages.

"A landmark in Mexican literature and one of the most influential books ever published in the Spanish language."

How can such a vast novel be so short? Juan Rulfo makes even the smallest scene pack a universe of meaning. Consider one of my favorite moments, when Juan Preciado, Pedro Páramo’s son, lodges at a lonely house near Comala, which is presided over by a brother and sister. Having no one to interact with but themselves, the siblings have become lovers, and when Juan Preciado discovers the nature of their relationship, he tells them so, to foster an “understanding” between them. To this, the brother responds, defiantly: “What do you understand?” His sister goes up to him, places her head on his shoulder, and repeats the same question. Preciado, dumbstruck, admits: “Nothing, each time I understand less.” In a few brief lines, Rulfo suggests several pages’ worth of characterization: how the siblings protect each other against an uncomprehending world, and how Juan Preciado, who has traveled from far away to meet the father he’s never spoken to, is overwhelmed by what he finds in Comala.

The dialogue and narration in Pedro Páramo are both poetic and conversational. Though not steeped in dialect – like, say, the Southern speech in American novels like Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn and Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree –, the novel uses regional expressions and words to evoke a Mexican setting. Examples include: "milpa" (maize field), "nixtenco" (stove), "otate" (cane), "parvada" (flock), and "papalote" (kite). All of these are specifically used in Mexico (and in some cases, also in Central American and Caribbean countries), and non-Mexican native Spanish speakers might have to consult their dictionaries.

"A good translation of Pedro Páramo, then, would need to capture this mixture of everyday language and powerful lyricism."

There also ordinary phrases, like "más te vale" – roughly translated as “you better (not)” – which Rulfo employs in significant ways. Near the beginning of the novel, Juan Preciado speaks to a strange woman, doña Eduviges. She asks him if he has ever heard the moaning of the dead, and when he admits that he has not, she warns him: “You better not have.” The narrative then cuts to a flashback, presumably a vision seen by Juan Preciado, in which it’s made clear that doña Eduviges is actually a ghost. Upon waking from the vision, Juan Preciado finds doña Eduviges still muttering: “You better not have, son. You better not have.” He had been hearing the moaning of the dead all along. This is a haunting illustration of how Rulfo uses colloquialisms for poetic purposes, repeating them like incantations and filling them up with new meanings. A good translation of Pedro Páramo, then, would need to capture this mixture of everyday language and powerful lyricism. Not easy, by any means, but necessary for such a precise and perfect novel.

There are, to my knowledge, two Mexican film adaptations of the book. The 1967 version, directed by Carlos Velo and starring American actor John Gavin, loses much of Rulfo’s poetry and seems rather Americanized, as if it were a Western in Spanish (Gavin is dubbed, obviously). Meanwhile, the 1978 version, directed by José Bolaños, is far better at capturing the melancholy and longing found in the original text, though it simplifies the narrative, has pacing issues, and looks like it’s set in Europe rather than in Mexico (it’s clearly influenced by Visconti’s The Leopard, about the decadence of upper class Sicilians in the 19th Century). Nevertheless, a definitive movie adaptation has yet to be made.