- L'œuvre

- Published by: N/A

- Level: Intermediate

- First Published in: 1885

L’oeuvre is the fourteenth instalment in the gigantic Rougon-Macquart series by Emile Zola, first serialized in the periodical Gil Blas, in 1885, before being published as a novel in 1886.

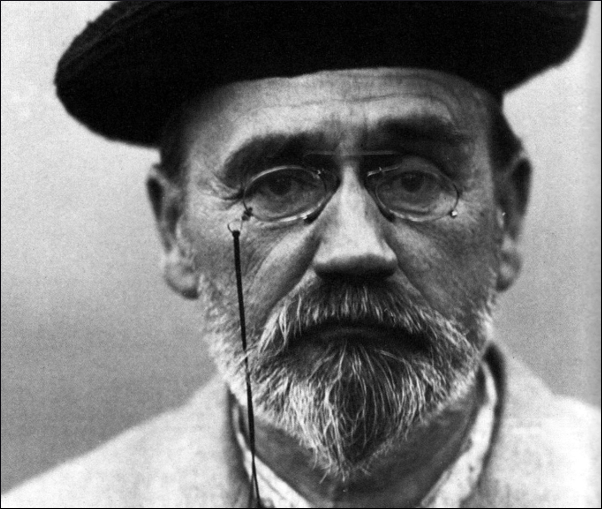

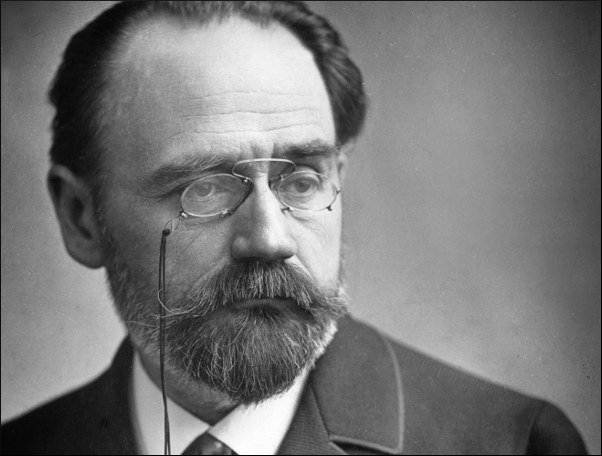

L'œuvre is a novel by Emile Zola, one of the most famous French writers of the nineteenth century, still widely read and appreciated in France. He is particularly renowned for his titanic Rougon-Macquart series, which depicts his contemporary society from the highest to the most miserable rank, quite a new ambition at the time. L’oeuvre is the fourteenth instalment in this gigantic series, first serialized in the periodical Gil Blas, in 1885, before being published as a novel in 1886.

"A novel by Emile Zola, one of the most famous French writers of the nineteenth century, still widely read and appreciated in France."

It tells the story of Claude Lantier, a descendant of the Lantier family, which was at the centre of previous instalments in the Rougon-Macquart series (his mother, Gervaise, is the tragic heroine in another book, L’assommoir). Claude is a struggling painter of much talent and ambition, but who faces misery as he refuses to indulge in the official and bourgeois taste of his time. His integrity, his total refusal to compromise, slowly leads him down the road from insouciant bohemia to sheer squalor, taking his muse (and partner) and their child along with him. The novel’s title has been translated to English in several ways, as The Work, The Masterpiece, and His Masterpiece. But the French original has a very interesting particularity, impossible to translate. “Oeuvre” has two main meanings in French, depending on whether or not it is used in its feminine or masculine sense. “Une oeuvre” refers to a single work, generally a work of art, while “un oeuvre” refers to the whole body of work of an artist, his complete catalogue. Within the book, it likely refers to the masterpiece that Claude attempts to finish throughout his life, endlessly destroying and redoing it, spending most of his energy and time on it.

Although he ruins his physical and mental health, and estranges himself from his friends and from the art world because of his obsessiveness, Lantier remains true to his ideals until the end. Yet, in so doing, he wastes his talent and wrecks his life. The book probes the consequences of choosing between bending to the demands of the public and following one’s ideals at all costs. Also, one of its most interesting aspects, besides its treatment of the above topic, is that the characters are all based on real personalities from the art world. Claude Lantier is said to be a portrait of Paul Cézanne, Zola’s childhood friend, himself depicted in the novel as Pierre Sandoz, a novelist who finds success. L’oeuvre is thus also a story about friendship and shared dreams. It is often said to have ended the beautiful friendship between both great creators, as Cézanne was not very pleased with being defined as an artist wasting his talents.

Even if Lantier is much like Cézanne, however, he combines many characteristics from other artists from the same generation and the previous one. Readers will enjoy figuring out who’s who, and for those who know the artists of the time, it will be quite an interesting task. Nevertheless, those who don’t know the history of art will still find this book interesting, as it vividly portrays the bohemian scene during Zola’s time, when artists freed themselves of the conventions of academic painting, going outside, “en plein-air,” to represent their contemporary world instead of reproducing mythological, historical, or allegorical figures. The depiction of Sandoz’s career also gives a moving account of Zola’s progression from penniless writer to renowned author, asking questions about integrity and lost ambitions, about success and sacrifice. L’oeuvre is probably Zola’s most personal book, bringing the art world into the kaleidoscopic reach of the Rougon-Macquart saga, describing a creative milieu whose difficulties and struggles against the establishment are still very much the same.