Officially, English Isn’t as Widespread as You Think

It’s obvious that English is the primary language spoken in the United States, but legally-speaking, only thirty-one states have English for their official language.

Today more states are considering language laws, so what’s the case for making it official? Here’s how language skills affect GDP in the UK.

Officially [American] English-Speaking States

Earlier this month the Washington Post published an article listing the five states deciding whether to make English their official first language this year. What would this mean exactly for these states, and what does it mean for the states that already have language legislation?

In Most Cases, Apparently Not Much

According to the Post, of all the laws in question the most severe belongs to Massachusetts. Massachusetts stands apart from other states in that the state’s supreme court recognizes the official language as English.

This came about in a 1975 case, Commonwealth vs. Olivo. A Spanish-speaking occupant of an apartment was convicted for failing to comply with an eviction notice written only in English, which she could not read.

For other states, however, these laws are more ambiguous. Illinois’s English law states, “The official language of the state of Illinois is English,” a mere acknowledgment.

The Missouri English law reads, “The general assembly recognizes that English is the most common language used in Missouri and recognizes that fluency in English is necessary for full integration into our common American culture” –recognition that gives no particular instruction in regards to state publications or otherwise.

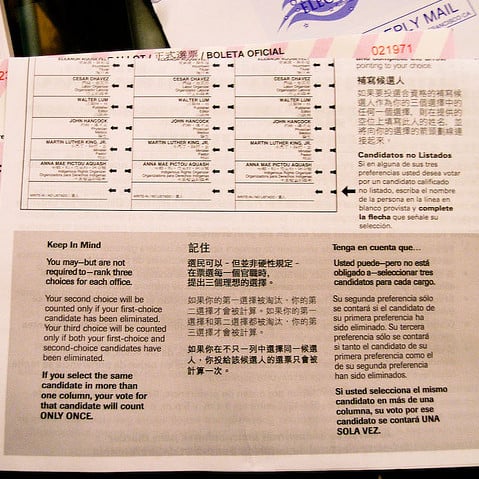

Unlike Massachusetts, other officially English-speaking states with additional guidelines do not usually enforce them. Many of these laws still allow for state documents to be translated. Examples are California and Arizona, who both have ballots in English, Spanish, and other languages in high concentration amongst their populations.

When these laws are often ambiguous and little enforced, why enact language legislation today?

A Nation of Immigrants (and Native Americans)

For U.S. English, a citizens’ action group dedicated to making English the United State’s official language, it is about English serving as “the bond that ties us together in our diversity.”

They also argue that it would save states money currently spent on printing documents in multiple languages as well as provide incentive for residents to learn English.

Discrimination against immigrants is the main basis for opposition to the federal amendment. The Obama administration falls on this side of the debate, yet a 2010 Rasmussen poll reveals 87% of Americans were supportive of making English the official language.

This year, residents of Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia will get the chance to put that sentiment into law or not.

Immigrants without competence in English are already a vulnerable population in the US. Without translations, they will be denied access to government services. Apart from the obviously discriminatory implications of official English laws, they also discourage bi/multilingualism, repress minority languages, and cultural diversity.

University of Illinois professor of English and linguistics, Dennis Barron, writes on PBS, “without legislation we have managed to get over ninety-seven percent of the residents of this country to speak the national language. No country with an official language law even comes close. Opponents also point out that today’s non-English-speaking immigrants are picking up English faster than earlier generations of immigrants did, so instead of official English, they favor ‘English Plus,’ encouraging everyone to speak both English and another language.”

As seen in most states today with official language laws, legislation may not necessarily include or carry out strict guidelines. These laws, though, would make a statement about the US’s relationship with immigrants. Not only will such laws remain unenforceable, they are unnecessary. There is enough incentive to learn English living in the United States already.

On the federal level, the lack of an official language requires the government to support residents with limited English proficiency under the Voting Rights Act. The 2011 American Community Survey states that their data is used primarily to determine how much of the population needs “translation services, education, or assistance in accessing government services” and where these populations reside.

Linguistic Melting Pot

Earlier this year, Slate’s Ben Blatt created a series of maps showing the languages spoken in the US homes besides English, using the American Community Survey’s data. An English Plus agenda seems to present a better way of garnering unity among Americans than an English-only one, and would celebrate the US’s cultural and linguistic diversity.

As the census shows millions of Americans speak languages other than English in their homes, and if more monolingual Americans learned an additional language, they may connect better with their neighbors. There is also the fact that learning another language highlights the structure of our own mother tongue and the ontology of American culture found in our dialect.

Language connects us more deeply with our own cultures and with one another. As Nelson Mandela famously said, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”

If you’re a native English-speaker inspired to embrace cultural diversity by picking up another language, consider improving proficiency in a foreign tongue like Spanish with a qualified language tutor. Language Trainers also offers a range of English courses, whether you’re brushing up on skills or starting from scratch.