Nerd Alert: Constructed Languages

You may think studying French for a language credit is a pain, but believe it or not, there are some people who are so enthralled by languages—linguists, social philosophers, writers and similar sorts—that they create entire languages and cultures to go along with them. These may be for practical use, for logical or philosophical experiments, or for artistic reasons, and they are more prominent than you may realize.

The most long-enduring International Auxiliary Language, that is, a language designed for functional reasons and meant to be spokenby people worldwide, is Esperanto. Esperanto was conceived in 1887 by L. L. Zamenhof, a linguist from Bialystok, a territory then in the Russian Empire which was later annexed by Prussia. Growing up in the midst of ethnic struggles, Zamenhof intended Esperanto to be a neutral language, easy to learn and with no irregularities, that would bring different nationalities together in peace and mutual understanding.

His dream did not go so well; Esperanto and its speakers were persecuted widely by the totalitarian regimes of the early 20th century, with Hitler especially taking offense to it, given Zamenhof’s Jewish heritage. (Mussolini, on the other hand, approved of Esperanto because it sounded similar to Italian.) But Esperanto has endured for many reasons: for one thing, as a hybrid of different Romance, Germanic, and Slavic languages, Esperanto can make a good foundation to learning any Western language. Today, up to 2,000,000 people speak it, but it has not yet broken its fringe status.

Láadan, a language created in 1982 by Suzette Haden Elgrin, is an example of a language engineered to explore a feminist theory. Elgrin suggested that Western languages are more suited to express the ideas of men than women and that a women-centered language would shape culture in an entirely different direction. (She also used Láagan in her Native Tongue science fiction series.) The main difference in Láagan is that the speaker’s emotion and intent are inherent in their grammar; six different articles of speech can tell you whether a sentence is declarative or interrogative, or it can indicate whether the statement is a command, a request, a promise, or a warning. Different suffixes can convey different levels of truth to the speaker’s sentence or the speaker’s feelings and mood. And, of course, female is the pre-assumed gender unless otherwise stated, with the suffix “id” making a word male. For example, the word “thul” can mean “mother” or “parent,” while “thulid” means “father.” Moreover, there are multiple different words describing menstruation, menopause, pregnancy, sisterhood, and mothers.

Perhaps the most widespread and imaginative of constructive languages are those created for artistic purposes, such as Orwell’s Newspeak or Lovecraft’s R’lyehian, the language of the Old Ones in his “Cthulhu Mythos” tales. And then there’s J. R. R. Tolkien, linguist and writer of the Lord of the Rings novels, who meticulously plotted out languages for every race in Middle Earth. The most beloved of these by fans are Sindarin and Quenyar, modeled from Welsh and Finnish respectively, the languages of the Elves.

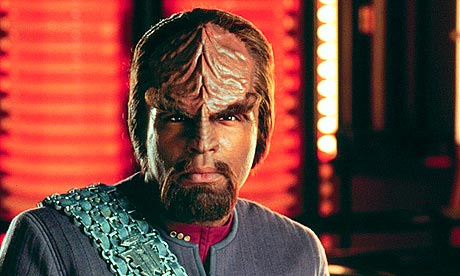

But the most popular constructed language of all time is Klingon, or as the Klingons call it, thlnganHol, the language of the alien warriors of the Star Trek universe. Linguist Marc Okrand specifically created it to be as complicated as possible, utilizing a confusing Object-Verb-Subject order to sentences. Since the first Star Trek movie, Klingon has developed into a comprehensive language with a complete grammar, vocabulary, and underlying culture. Fanatics have translated works from Shakespeare to Sun Tzu to The Bible into Klingon. There’s an opera, u, composed entirely in Klingon. There’s even a Klingon Language Institute dedicated to the study of Klingon language and culture. Clearly, Okrand has done more than create a language—he’s engendered a cult following.

Constructed languages, although manufactured, can clearly grow and evolve to serve human needs just as well as natural languages. Many have global communities dedicated to their growth and preservation, and there are countless resources online for learning Esperanto, Klingon, or Sindarin. Even if you don’t commit to learning an entire dictionary, why wouldn’t you want to learn a couple of phrases in the tongue of the Grey Elves, or the Cthulhus, or the community of science fiction Amazons? At the very least, you’ll be a hit at parties.

Do you know of any other constructed languages?