Using Forensic Linguistics to Solve Mysteries and Fight Crime

Language is a broad topic that relates to many different aspects of our lives. It has the power link people and bond communities and the ability to completely destroy relationships. You can use it to create illusion or even sometimes solve a mystery. That latter case is something of particular interest for a more serious matter. Are you ready? See what happens when an unsolved series of murder cases meets with forensic linguistics and learn about the true power of the words that we use.

Photo via https://pixabay.com/en/fingerprint-expression-328992/Wikimedia

The story begins

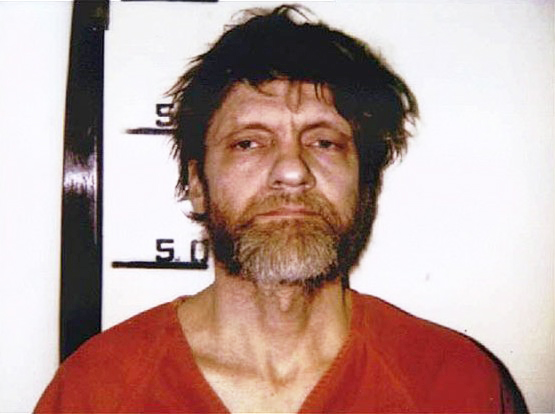

Twenty years ago, Ted Kaczynski pleaded guilty to all charges brought against him by federal prosecutors. The man, more infamously known as the Unabomber, killed three people and maimed 28 others with homemade bombs over an 18-year period. However, unlike many other serial killers who are brought to justice by DNA evidence, it was forensic linguistics — or the use of linguistics knowledge, methods and insight to solve and prosecute crimes — that caught the former Harvard graduate and University of California, Berkeley professor.

Kaczynski was exceptionally smart with an IQ that measured off the charts. He was very careful in constructing and sending his bombs and left no DNA evidence that could be used by investigators. The FBI spent nine years and millions of dollars looking in vain for someone whom they knew next to nothing about. The big break in the case came in the 1990s — roughly 15 years after he sent the first letterbomb — when the Unabomber began to send letters to the media discussing both his crimes and sometimes his victims.

The power of words

He was very articulate and spoke using a particular and out-of-date vernacular. This is what gave FBI profiler, James Fitzgerald, the idea to use linguistics as a way to catch him. “I said, I want to devote my time and energy to looking at the language in this case and let’s see just what the heck I can make out of it,” Fitzgerald told NPR in a 2017 interview.

Photo via Pixabay

Fitzgerald had a hunch that by using clues in the Unabomber’s letters, the FBI would be able to create a much stronger profile. Some of the Unabomber’s word choice also hinted at his age. “Before too long, I’m picking up on some unusual language characteristics, like some archaic terms like ‘broad’ and ‘chick’ to denote women,” Fitzgerald said. “He uses the word ‘negro’ to refer to African-Americans. And this is 1995, and these words were almost like Frank Sinatra language, or something you’d hear from a ‘50s movie or something. And right away, that helped me age the author.”

Then Roger Shuy, a linguistics professor, used the same letters and methodologies to figure out where the Unabomber was originally from. “He thought this writer of the manifesto had his roots in Chicago because there was some terminology in there that was reflective of three or four newspapers in Chicago,” Fitzgerald said. “And the first four bombings were either placed or mailed from Chicago, so it’s always nice when you have a nexus that you can sort of compare here, and they match up.”

However, the later bombings mostly took place in California with one going off in Utah. Fitzgerald and the FBI knew he must have relocated, but did not know when. The trail was going cold until in 1995 when the Unabomber contacted the New York Times and Washington Post about publishing his dystopian, 35,000-word manifesto. At the urging of Fitzgerald, they eventually published the manifesto, hoping that someone would recognize the writing.

And someone did

David Kaczynski, Ted’s brother, was shown the manifesto by his wife. He recognized the writing style immediately to be his brother’s. David went on to send the FBI a similar piece of writing he had received from his brother many years ago. “They sent me this thing and not only did the format match, but it was actually written in the same chronological order as the manifesto, lots of the same terms,” Fitzgerald said. “I realized to myself, this is essentially an outline, a well-crafted outline of the manifesto.

One phrase, in particular, stuck out. Ted had used, “eat your cake and have it, too” in a letter to the manifesto as well as the outline that David had provided to the FBI. This really stuck out. The conventional wisdom was that the phrase was supposed to be inverted: “You can’t have your cake and eat it too”. However, Kaczynski’s use proved to be correct. The inversion happened as the language evolved from Middle English.

Following the trail of clues

Fitzgerald saw smoke, but now his burden was to prove that there was fire. With the help of David, they tracked Ted down in Montana, but needed a warrant to search his hand-made cabin. The judge in the case was hesitant to issue the warrant. Using solely forensic linguistics had never been done before and there were no real experts to call upon and corroborate Fitzgerald’s findings. However, the warrant was eventually given and the FBI raided Ted’s cabin.

Photo via Wikimedia

Inside they found the smoking guns: along with bomb-making materials, the FBI discovered a manual typewriter and Skrunk and White’s Element of Style, which was the same style in which the manifesto was written. Further analysis at the University of Michigan, where Ted received his PhD, added linguistic evidence to the case and furthered his “linguistic fingerprint”, which investigators were now using to tie him to the crimes.

After all of the evidence mounted up against him, Ted Kaczynski pleaded guilty to all charges and was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

The mystery was solved

James Fitzgerald went on to become the FBI’s first forensic linguist, and later earned a Master’s in Linguistics.

Since this episode, forensic linguistics has become a crucial part of how crimes are solved. Since the Unabomber’s confessions, forensic linguistics has helped solve wiretap cases, identify ransom note, text, tweet, and email authors, and even solved a murder in which the key witness was a parrot!

Has language ever helped you solve a mystery? If so, share your experience below!