China Takes Action Against Puns

It may sound like the headline from a satire news site, but China was dead serious when its State Administration For Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television officials issued a mandate against puns, idioms, and other forms of wordplay in the media. By means of backing up this decision, China has offered the somewhat flimsy explanation that puns lead to “cultural and linguistic chaos.” They claim that punning impedes the promotion of cultural heritage and can lead to widespread confusion, especially for children.

While on the surface, this seems ludicrous at the most extreme, it becomes more sinister when you consider the context of China’s language and culture. As Chinese is a tonal language, with very subtle differences between the sounds of syllables, it is rife with homophones, making it perfect for very elaborate punning. In fact, puns are so deeply intertwined in Chinese heritage—for example, the tradition of giving newlyweds dates (zao) and peanuts (huasheng), because of the similar sounds to the wish that they might have a son: Zaosheng guizi—that an attempt to clamp down on them can easily be interpreted as violence against China’s widespread folk culture.

Even more tellingly, a culture of puns and double entendres has evolved in China as a way to sidestep censorship. In fact, Chinese internet users have developed an entire lexicon of terms, many of them initially puns, so they can contribute to political and social forums unhindered. For example, the Chinese word for river crab, hexie, is similar to the word harmony, commonly used to refer to media censorship or distrust of a government agenda; a subversive post that has been blocked by the government is generally described as being harmonized.

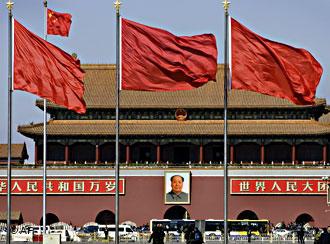

A common term that has raised red flags on social media is the mention of May 35th, a code name for June 4th, the day the army arrived at Tiananmen Square in 1989 to suppress demonstrators—on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter. Any mention of May 35th, June 4th, or even phonetic homophones of the numbers six and four are blocked. Another wordplay involves Mao Zedong’s political slogan, “Serve the people,” in which “serve” is replaced with “smog” (both words are pronounced wu in Chinese), connoting an erasing or obliterating of the population by its leaders.

Serious political discussions aside, it is likely that China has levied its ban on wordplay simply to keep from being made ridiculous by such tongue in cheek puns as its current government being referred to as entering “the Dama Era,” a comment made by a Weibo user combining the first syllables of Daddy Xi and Mama Peng (the President and First Lady). In Chinese, dama is a homonym for marijuana. However, with pressure from outside countries to increase personal freedoms for its citizens, China will soon discover that keeping one billion people in perfect check may not be worth the trouble. And, in light of the Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong and widespread dissension elsewhere, many have pointed out that this may be the Chinese government’s last-ditch effort at proving they’re in control.

If you would like to learn more about China’s fascinating capacity for word games, send us an inquiry about information on our Chinese language courses, or take a free online Chinese language level test.